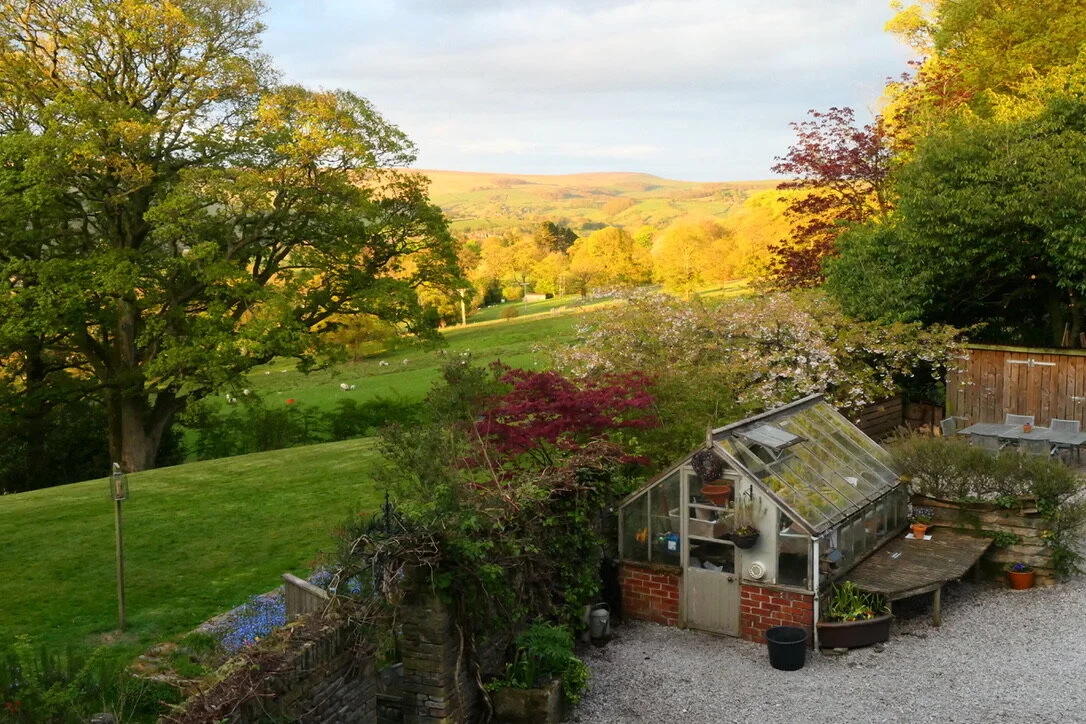

Spring, 2020 Whitehough, Derbyshire, the English Midlands

The Corona Virus and the wide spread disparate measures across and within different countries, prompted me to reconsider the issue of rights and responsibilities. I have no developed formal definition of these terms, other than to consider them coupled and inseparable, and to harken back to the simple precept: “do unto others what you would have them do unto you.” It means that one should be aware of one’s actions on the well-being of others; to understand that actions have consequences. One is not a ‘free agent’, ever, because humans are inescapably social. We don’t live as isolated hermits, responsible for every aspect of our daily life. We are inextricably interdependent. Common good cannot be achieved absent the practice of responsibilities along-side of that of rights.

In democracies, rights and responsibilities are framed by law. In the U.S., we have a Bill of Rights, rights of freedom of expression, rights to life, liberty, and happiness, rights to equal protection, and more, firstly aimed at protecting the individual from egregious acts of the state. Such protection from the state is historically based, a legitimate revolution against arbitrary tyranny as was exercised by sovereigns in monarchies and dictatorships.

Today, these rights are seen as essential for a just society, one in which everyone can thrive equally, protected by the law. But critically, these rights do not exist independently of their defense, of respecting those rights, and behaving in such a way so as to not violate them. This is where responsibility comes in. The right to equal protection only is possible when it is respected and people (or the state) do not engage in actions that violate it; this includes equal protection from exposure to a virus that might entail someone else wearing a mask. It entails equal protection from discrimination due to one’s color, sexual orientation, religious belief, and so it leads one to ask whether the higher incidences of Corona Virus among poor people of color in the US is not a violation of their equal protection. A violation of employees by meat packing monopsonies, or by Amazon, or by a society that has rejected confronting white hegemony and privilege shows the erosion of rights before the law.

The difficulty in the early Twenty-first century, is the question of individual sovereignty (as well as the sovereign state) when a pandemic requires cooperation and solidarity, and the exercise of responsibility, beyond those sovereign categories (Van Kooy, personal communication). Just as the Bill of Rights was formulated at a time when the shadow of arbitrary state power was in living memory (it may be returning again), the challenge of facing a global pandemic that also reflects enormous societal inequalities, may challenge the notions of sovereignty. We need to develop a new frame, new vocabularies and new values that reflect a new way of thinking of ourselves as social creatures. Yes we are individuals, but individual rights alone no longer work as a point of departure (Judith Butler Lecture on line). We are situated in a world together – I can catch your virus – I am harmed when you are suffocated by a policeman –– we are inextricably bound -- here is no escape.

The United States Conference of Bishops states that the “Catholic tradition teaches that human dignity can be protected and a healthy community can be achieved only if human rights are protected and responsibilities are met. Therefore, every person has a fundamental right to life and a right to those things required for human decency. Corresponding to these rights are duties and responsibilities--to one another, to our families, and to the larger society [bolded by me]. No right to freedoms or to life and human dignity can exist without a corresponding sense of responsibility that creates the social fabric where such rights can be exercised and protected.”

Buddhist beliefs are founded in the Noble Eightfold Path, a code of conduct that embraces nonviolence, freedom from causing harm and a commitment to intentional ethical behavior. Buddhist practice involves a commitment to developing right action, one that does not do harm, on cultivating heedfulness and mindfulness: paying attention to one’s actions and to their possible consequences. Being a Buddhist is about becoming a responsible and ethical member of society, accountable for ones’ actions, if only through Karma alone.

All religious faiths have embedded in them the need for responsible, ethical action. In secular democracies, responsible action is often codified into law, including in the U.S., as with the Bill of Rights. The enforcement of laws helps to create trust in a society, trust that rights will be protected, and that irresponsible behavior will be punished. But beyond law enforcement, in daily life, we rely on people to exercise their rights responsibly, to understand that their behavior has consequences on society, and on others. And in a world where pandemics and a changing climate transcend boundaries and further inequalities, it is important to reengage in a commitment to exercising rights responsibly.

Yet, in today’s discourses, it seems that rights alone should prevail, at least in the U.S. Wearing a mask or not, social distancing or not, are a flash points today for the ways in which “rights” have increasingly been asserted: rights detached from the well-being of others in society. The social compact that ensures rights can endure is dissolving as people reject and or forget that they need to be responsible for their actions. It is as though their entitlement supersedes the welfare of others, that they, somehow, are outside of the commonweal and immune from the consequence of their acts. The proclaimed right not to wear a mask likely will means that others will get sick and die needlessly. It is like the ‘right’ to yell fire in a crowded room that causes mayhem and fear. This is not the exercise of a right, it is the exercise of the unmoored and disaffected, the angry and abandoned by the body politic, the neglected and the unhappy. It seems more prevalent in countries where income differentials have grown, where there are increasingly high rates of poverty, weak public education and health care, and deep alienation. Where the responsibility of society toward all its members has not been fulfilled, distrust, hostility and an assertion of harmful acts posing as rights have filled the vacuum.

There is no question that the implementation of measures to protect public health during the pandemic involve the curtailment of our habitual behaviors – sheltering in place, the wearing of masks, and washing of hands, the social distancing. That these measures can be seen by some as an infringement on individual or personal rights shows a lack of understanding of the rights of individuals in a democracy. Wearing a mask does not undermine the rights inscribed in the Bill of Rights and the protections of the law. Violating public health precautions is of a different order – it is a reaction against precaution, a hostile stance toward society. It proclaims individualism above social solidarity and a right to inflict harm on others with no consequences.

Rights are not superficial entitlements, equated to the right to choose consumer goods and to construct one’s individuality through what product gets bought shaped by unrelenting advertising. Rights are of a different register, they reflect a gravitas about how we construct our social lives together, and together globally. They are about realizing that rights are made possible only through compassion and responsible action by others. Through commitment to duty, an old fashioned concept that implies responsibility (Jaurretche personal communication), all rights are protected. With no accompanying responsibility for exercising a right, that right is trivialized and thin, it becomes a reactive stance rather than something thought about and taken seriously. Those asserting their rights in the face of Corona Virus precautions are jeopardizing the health of others, especially as we have seen, among the poor and the vulnerable. Countries refusing to develop strong public health precautions to take care of their residents, are undermining global stability in the name of national sovereignty and undermining trust – the trust that one can travel to other places and be safe. Personal sovereignty, national sovereignty are not of importance to a pandemic virus. They are inadequate to address the interconnectedness among us all, that binds us all together as human animals, vulnerable to disease, whose better survival depends on solidarity.

So what is at the heart of this irresponsible behavior? Hannah Arendt gave a great deal of thought to the question of responsibility in trying to understand Eichmann’s role in facilitating genocide. She put forward a theory about Eichmann that seems highly applicable today, and has perhaps not gotten the attention it needs more broadly. For Arendt, Eichmann’s culpability was that he did not think. According to Judith Butler, Feminist Philosopher at UC Berkeley, Arendt asserted that no thinking-being can plot or commit genocide; could the same be said about the almost off-handedness with which some leaders have addressed the Corona Virus? These leaders are not thinking beings. The process of thinking is an active acknowledgement of being in a society, in a plurality. Not thinking destroys that plurality, society, and thus part of one’s self. For Arendt, thinking and responsibility are bound together, part of politics and ethics. Arendt’s analysis goes far beyond my simplistic rendition of the importance of thinking and its implications for acting responsibly, but at an intuitive level, one can grasp the meaning of the insight. What we are experiencing at the highest levels, and replicated in a certain sliver of the public, is a lack of thinking, a lack of accountability for the maintenance of rights through the practice of acting responsibly, which comes from thinking. This has huge implications for the norms that govern political life. If anything goes, and it’s just a matter of reacting moment-to-moment putting one’s self interest first, then the social contract falls apart, and rights dissolve in the face of solipsistic decision-making. President Trump, Prime Minister Johnson, Presidents Bolsonaro and Duterte, among others, appear to lack introspection sufficient to think about their moral responsibility, a quality that is needed when one exercises rights, and leading countries. They exercise the power of the decision maker, but they do not accept the bounds that come with that power, the bounds of responsible action articulated in their oaths of office. They are not committed to the rights afforded in democracies: life, liberty, happiness, freedom from oppression and discrimination. And they are not thinking about the effect globally, on other countries.

Rights live in a moral and ethical universe. They come from struggle and commitment, from the acceptance that there are duties and one does not simply have entitlements. Living responsibly, exercising judgement and thinking are also foundational to trust. Trust is fundamental to human interactions. I need to trust you will exercise your rights responsibly so I will not be hurt. Rights emanate from understanding the consequences of irresponsible behavior – from behavior that is not guided by responsible rights, where individuals or the state act volitionally, arbitrarily and violently. A global pandemic cannot be met with self-indulgent rights talk that is unthinking of social responsibility, centered around the sovereign individual. It cannot be met with nations that proclaim their exceptionalism, and independence from others’ conditions. It cannot be met by waiting for herd immunity to ravage the poor and people of color. It can only be met by exercising responsible behavior, by thinking of consequences, and not just for one’s self.

__________________________